The *Trolley* Triage

With a little imagination, it is not hard to visualize Eduardo Morales feat of engineering as acting out in real time a classic thought experiment in the study of ethics and morality.

With a little imagination, it is not hard to visualize Eduardo Morales feat of engineering as acting out in real time a classic thought experiment in the study of ethics and morality.

Morales was shuffling train cars with his engine at the Port of Los Angeles in San Pedro when he (self-admittedly) “snapped” and engineered (drove?) his locomotive engine off the end of the track and toward the hospital ship USNS Mercy. The ship was tied up at the port for the purpose of handling hospital patients in the area to leave room in the land hospitals for an influx of COVID-19 patients. Morales seems prone to latching onto conspiracy theories—and in this case his own, as he thought there were sinister motivations and implications of this ship being there, a government plot, and takeover, and obviously something to do with the virus. And like so many conspiracy-motivated acts of violence, was unsure of any actual plans or hard evidence to carry out whatever it was to happen.

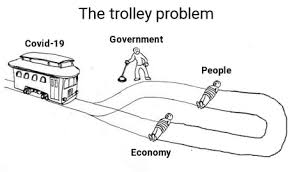

The Trolley Car Dilemma (*trolley*–should be streetcar to us in New Orleans) has been used to start deep discussions and nurture lively debates since the 1960s. It has evolved many iterations, but all have to do with thoughts about “the consequences of an action and consider whether its moral value is determined solely by its outcome.”(1) The first and most basic version has one imagining a *trolley* (the train engine is a perfect substitute) heading down a track where five inattentive or otherwise unaware workers were going to be hit and probably killed by the unstoppable *trolley*/train. There was a switch on the tracks that could divert the engine to another track, and bypass the five, but the alternative track had one worker on it, also oblivious to any approaching danger. So in one version, there is a switchman that can pull the lever and send the *trolley* down the track toward the lone workman—in another version it’s the engineer himself who can somehow steer the train down the the second track and take out the one worker there, sparing the five on the first route. So can we justify taking out one person to save five? The utilitarian-consequentialist will immediately figure this is a net saving of four lives, and the better and therefore justified action. Is it? Could you feel comfortable with this steering decision?

Had Morales been aware that some amateur blogger on a humanist website would have made the connection of this classic puzzle to his actions, he might have tried to rationalized the possible danger his dangerous mishandling of a locomotive as it stacked up against the evil contained with the presence of the hospital ship docked very near his freight yard. But he confessed to the authorities that he didn’t really know what dangers or schemes were interwoven with the ship’s mooring, and what, if any, better outcomes were to be realized had this pathetically failed terrorist mission succeeded; and that no one “was pushing his buttons,” but he could “draw the world’s attention to it”—whatever “it” was.

Immanent and ongoing medical triage presently in global locations strains medical staff and equipment sometimes to the breakdown point and are forced to make priorities, choices, and metaphorically substitute one for many—based on health, age, history–ranked on a scale. Who gets a ventilator first if two are waiting and one is available? Should much needed medical supplies be sold to retail merchandisers and resold for profit? Should mandates be put in place to enforce healthier foods? Is the US Government emergency supplies belong to someone other than the citizens of the nation? These are all tracks and spurs of an emergency medical and economic triage, and one is hoped to make a good ethical choice at each fork or binary switch, much like the *trolley* problem.

Historically, there are seldom large-scale epidemics of illness or disasters of war which the medical community can keep up with the demand for its services. Good management is about as good as it gets we have been taught. There is little money to be made buying and storing equipment that can become obsolete before it is ever used, the legislative budget writers always have triaged armaments for fighting human enemies as a higher priority. Scott Ploof with Big Easy Magazine writes “Our healthcare is much more important to our livelihood than the economic system that prioritizes wealth at the sacrifice of our health.” About this economic system, secular humanist and democratic socialist Martin Hägglund says “The key to the critique of capitalism is therefore the revaluation of value. The foundation of capitalism is the measure of wealth in terms of socially necessary labor time. In contrast, the overcoming of capitalism requires that we measure our wealth in terms of what I call socially available free time.” (2).

A revaluation of value—is this even possible on a grand scale? Turning the metaphorical train would seem to be more daunting than turning an actual *trolley* 180° on its track. Once we have gotten this deep in the maze of spurs on spurs of miles and miles of tracks and time passed, is it possible to back out of it? Given the prospects of likely future pandemics, climate catastrophic, nuclear warfare, and environmental poisoning, such a revaluation of value would seem to be necessary if humanity is to thrive, or just survive on this planet. Any other choice heads towards a flamboyant nihilistic end, such as Eduardo’s last trip behind the controls, reminiscent of Slim Pickens as Major T. J. “King” Kong straddling the bomb in Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb whooping it up, cowboy hat in hand.

At the last minute, Moreno lit a flare. He looked up at the camera, raising his middle finger to it. Then, just before the train smashed through the concrete barriers, he stuck the flare out the window, keeping it there all the way through impact.

He told the detectives, “I can’t wait to see the video.”

(1)https://theconversation.com/the-trolley-dilemma-would-you-kill-one-person-to-save-five-57111

(2)Martin Hägglund. This Life Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom. New York: Pantheon Books, 2019. Socially available free time is an expansion of Marx’ concept of socially necessary labor time and refers to that part of life that should be dedicated to, and part of, flourishing, and not just existing. Recommended reading.

Details and quotations of the Morales episode were found in the Washington Post article

https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/02/train-derails-usns-mercy-coronavirus/

Marty Bankson reporting for The Humanist Advocate

April 5, 2020