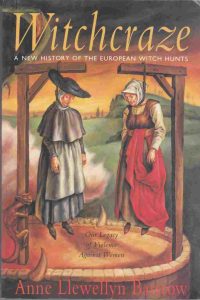

BOOK REVIEW: Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts

The literature, both scholarly and fanciful, on the European witchcraze is voluminous and of uneven quality. It was a pleasure, then, to find a work of scholarly quality that stands out for its unusual perspective. Historian Anne Llewellyn Barstow has studied the phenomenon from a much need feminist perspective in Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts.

There is far less here, than in many other studies of the same phenomenon, about religion and beliefs about witchcraft, and a lot more about the roles of women and men, and changes in the social and economic structures of Europe during the worst years of the witchcraze (1550-1750). Barstow sets the number of persons executed for witchcraft during that time at roughly 100,000, a lower figure than some other historians, and admittedly an estimate from incomplete sources. This does not mean she casts the witchcraze in a more positive light than others. In fact, she shows that a very large percentage of the accused and executed were women, and is careful to demonstrate the cloud of fear under which European women lived for those centuries, the nearly absolute lack of fairness or objectivity toward the accused, and the sexual sadism of the processes of interrogation and execution.

Why that time and that place? Barstow takes a multifactorial view. The roles and opportunities for European women had been narrowing for centuries (and would continue to narrow until well into the 19th century). The early rumblings of Capitalism were actually increasing the gap between rich and poor, and women who owned property but had no male protectors became especially vulnerable. Two religious movements, the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, generated a drive toward orthodoxy that included formal control of sexual expression as well as of religious doctrine. Increasingly centralized religious and governmental power meant more intervention by authorities into local and private interactions. Witchcraft came to be seen as not merely heresy, but as a crime against the state.

In a brief but fascinating analysis, Barstow points out that the era of the witchcraze corresponds roughly with the age during which Europeans enslaved Africans. This is no coincidence. Barstow writes (pp. 159-160):

“We need to see the similarities between all women in a patriarchal system and all persons in an unfree status . . . . free women and slaves of both sexes fell into many of the same categories in the eyes of early modern European men. Neither had control over what they produced, other than in exceptional circumstances, and their labor could be coerced. Both were seen by the law as children, as fictive minors who could be represented in court only by their masters/husbands. Both could legally be beaten, debased, and humiliated. When mistreated, both were impotent to gain help from others within their group, nor usually could their families help them.”

For readers interested in what early modern Europeans thought witches actually did and why, Kramer’s (ca. 1486) inquisitorial handbook Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer against Witches) is indispensable. A similar insider’s view of the Salem witch hunts can be found in Cotton Mather’s (ca. 1692) On Witchcraft. But the Malleus and On Witchcraft are products of their respective times and places, making no attempt to place paranoia about witchcraft in a social and historical context. Anne Barstow’s Witchcraze helps make sense of the nonsense.

Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, by Anne Llewellyn Barstow (1994). Pandora/HarperCollins; ISBN 0-06-2500049-X.