On NOSHA @ 20, and Living On

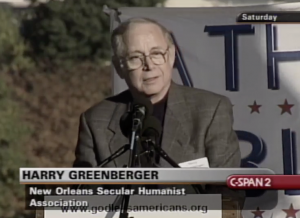

Even it its early years, the collective and evolving group of individuals of the New Orleans Secular Humanist Association was already developing an ethic of action—working together and getting things done to make its ideology known and its principles something to be reckoned with— owing in no small to the commitment of its first president Harry Greenberger and other founding and early members. In this c-Span video from 2002, Greenberger shares some of the accomplishments of our small-group organization, and asks a small group of atheists, and all others within earshot of the symbolic people’s megaphone that is the National Mall in Washington, what they can do:

Harry on the Mall, 2002

This month is twenty years since that collective of freethinkers and skeptics first sat down at the Barnes and Noble bookstore to address their common concerns of which no forum in our city had previously existed to do so. This meeting in 1999 preceded the explosion of popularity of atheism and scientific naturalism—led by the New Atheist movement—by a half-dozen years, and foreshadowed the proliferation of non-theist groups and chat rooms on internet social media by almost 10 years . Its concerns about the never-ending quest of the religious community to author public legislation based on Biblical moralities, its relentless attempts to gain control of educational agendas and curricula in our public schools, and its advocacy of political grifters and judicial appointees sympathetic with them; and the concern, on a more philosophical level, of the futility of continuing to propagate and encourage magical thinking, to spin fantastic, evidence-free theories of life and its origins and ends, and to devalue our only true life experience with empty promises of existing into eternity.

But concerns are just the beginning, and just linger, then fester if left to stew. Addressing concerns to achieve favorable real life resolution and catharsis —partially or in toto–requires actions similar to those our evolving group has maintained since the beginning, most having to do with education through our monthly programs and special events and field trips, cable television interviews, and delivering secular invocations at city council meetings; and putting in real sweat equity or cash into community service projects and donations to disaster relief funds. It was, at that point, mostly an example of “determinism without a blueprint”

But what can keep us going on, given the continual setbacks our worldview has suffered—and every positive advance seems to be met with even more reversals in the educational, cultural, and political realms? How can we encourage and get more participation from our members? We are celebrating our twentieth birthday, but what, if any, guarantees there will be a twenty-first?

But then again, what guaranteed the group of soon-to-be NOSHANs at that first meeting would gather for a second meeting, or ever again?

If you were browsing the shelves in that Barnes and Noble—or any other book vendor, for that matter—and your eyes crossed paths with a book wearing a dust jacket sporting a soft, printed impressionist pastoral scene in pale ochres and siennas, with a title like “This Life” and were previously unfamiliar with it, you might, without hesitation, continue focusing right on past it. I know I would: “o’boy, another sentimental and meandering tale of hardship and happiness, a story about….what–ever!!” A closer look at the subtitle might cause you to hesitate: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom. There’s that word, secular; this book just might have something to do with me. You would be right.

Martin Hägglund’s recent book (1) bearing that title is the most thoroughly developed exposition on most all things in life concerning ethics, morality, meaning, value, and purpose from a secularist’s perspective in recent memory. One would need to go back to the classics of Aristotle’s Nicomachean ethics and through to Marx’s theory of freedom to hint at the scope of Hägglund’s work. I would refer to just one of his major points and how it relates to the past accomplishments and future viability of our organization. It turns on a term to which our standard empirical demand on evidence does not apply, a word toward which many of us raise a skeptical eyebrow when it comes up in discussion. The term is faith.

As a first principle, the humanist must accept that life is worth living. There is no evidence for this, as evidence for axiological claims is notoriously elusive, but the converse of this proposition is simply a non-starter, nihilistic and self-destructive. We must also accept that there is only one, very limited life for anyone born, and that that life is fragile, finite, and can go wrong in so many ways, and sooner or later will be lost—forever. Taken from the introduction of This Life , these snippets show where he is going with his theory of secular faith.

“The sense of finitude—the sense of the ultimate fragility of everything we care about—is at the heart of what I call secular faith. To have secular faith is to be devoted to a life that will end, to be dedicated to projects that can fail or break down….I will show how secular faith expresses itself in the ways we mourn our loved ones, make commitments, and care about a sustainable world. I call it secular faith because it is devoted to a life that is bounded by time…To be finite means primarily two things: to be dependent on others and to live in relation to death. I am finite because I will die. Like wise, the projects to which I am devoted are finite because they live only through the efforts of those who are committed to them and will cease to be if they are abandoned…I call it secular faith, since the object of devotion does not exist independently of those who believe in its importance and who keep it alive through their fidelity…Secular faith is committed to persons and projects that may be lost: to make them live on for the future. Far from being resigned to death, a secular faith seeks to postpone death and improve the conditions of life…The commitment to living on does not express an aspiration to live forever but to live longer and live better, not to overcome death but to extend the duration and improve the quality of a form of life.”

Hägglund makes it clear that there is no eternity and no unbounded human life; there are only brief and tenuous lives with no guarantees—other than that they will end, as will all the projects and commitments those lives have concerned themselves with. In our case, the only chance for another year or another month for NOSHA surviving is quite dependent upon enough people to believe that it is a project worth doing, all the while knowing that it may weaken, fragment, or dissolve totally into a thing past.

And we can, during our 20th anniversary remembrances and tributes, offer a word of mention to the original group at that first meeting at Barnes and Noble who have kept that secular faith and helped take NOSHA this far along in time, and to this day continue to be active to some degree in our project. Will Hunn—Charlotte Upadhyay—Tom Stine—Dave Schultz—Denis Dwyer—Lucy Tierny—Michael Malek—Darlene Reeves— first held, and then kept, the secular faith in that NOSHA was, and continues to be, a project worth doing. They, and many others who came along later to begin drawing and tweaking the blueprint, are responsible for NOSHA living on.

Marty Bankson, reporting for The Humanist Advocate, NOLA

Special thanks to Dave Schultz and Denis Dwyer for providing all of the details about NOSHA’s first meeting

(1) Hägglund, Martin. This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom. New York: Pantheon Books, 2019.