From the Dead God Files

“On Angels”

by Donald Barthelme

The death of God left the angels in a strange position. They were overtaken suddenly by a fundamental question. One can attempt to imagine the moment. How did they look at the

instant the question invaded them, flooding the angelic consciousness, taking hold with terrifying force? The question was,”What are angels?”

instant the question invaded them, flooding the angelic consciousness, taking hold with terrifying force? The question was,”What are angels?”

New to questioning, unaccustomed to terror, unskilled in aloneness, the angels (we assume) fell into despair.

The question of what angels “are” has a considerable history. Swedenborg, for example, talked to a great many angels and faithfully recorded what they told him. Angels look like human beings,

Swedenborg says. “That angels are human forms, or men, has been seen by me a thousand times.” And again:”From all my experience, which is now of many years, I am able to state that angels are wholly men in form, having faces, eyes, ears, bodies, arms, hands, and feet…” But a man cannot see angels with his bodily eyes, only with the eyes of the spirit.

Swedenborg has a great deal more to say about angels, all of the highest interest: that no angel is ever permitted to stand behind another and look at the back of his head, for this would disturb the influx of good and truth from the Lord; that angels have the east, where the Lord is seen

as a sun, always before their eyes; and that angels are clothed according to their intellige

nce. “Some of the most intelligent have garments that blaze as if with flame, others have garments that glisten as if with light; the less intelligent have garments that are glistening white or white without the effulgence; and the still less intelligent have garments of various colors. But the angels of the inmost heaven are not clothed.”

All of this (presumably) no longer obtains.

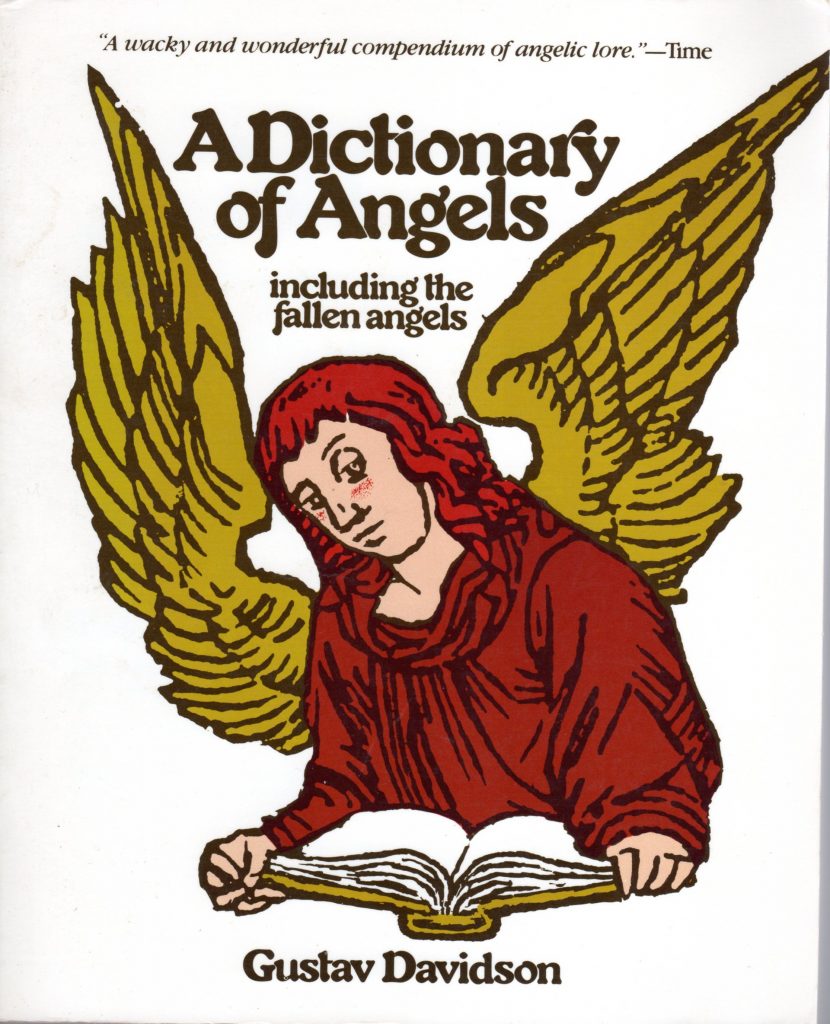

Gustav Davidson, in his useful Dictionary of Angels, has brought together much of what is known about them. Their names are called: the angel Elubatel, the angel Friagne, the angel Gaap, the angel Hatiphas (genius of finery), the angel Murmur (a fallen angel), the angel Mqttro, the angel Or, the angel Rash, the angel Sandalphon (taller than a five hundred years’ jouney on foot), the angel Smat. Davidson distinguishes categories: Angels of Quaking, who surround the heavenly throune, Masters of Howling and Lords of Shouting, whose work is praise; messengers, mediators, watchers, warners. Davidson’s Dictionary is a very large book; his bibliography lists more than eleven hundred items.

The former angelic consciousness has been most beautifully described by Joseph Lyons (in a paper titles The Psychology of Angels published in 1957). Each angel, Lyons says, knows all that there is to know about himself and every ohter angel. “No angel could ever ask a question, because questioning proceeds out of situation of not knowing, and of being in some way aware of not knowing. An angel cannot be curious; he has nothing to be curious about. He cannot wonder. Knowing all that there is to know, the world of possible knowledge must appear to him as as ordered set of facts which is completely behind him, completely fixed and certain and within his grasp…”

But this, too, no longer obtains.

It is a curiosity of writing about angels that, very often, one turns outto be writing about men. The themes are twinned. Thus one finally learns that Lyons, for example, is really writing not about angels but about schizophrenics–thinking about men by invoking angels. And this holds true of much other writing on the subject– a point, we may assume, that was not lost on the angels when they began considering their new relation to the cosmos, when the analogues (is an angel more like a quetzal or more like a man? or more like music?) were being handed about.

We may frther assume that some attempt was made at self-definition by function. An angel is what he does. Thus it was necessary to investigate possible new roles (you are reminded that this is impure speculation). After the lamentation had gone on for hundreds and hundreds of whatever the angels use for time, an angel proposed that lamentation be the function of angels eternally, as adoration was formerly. The mode of lamentation would be silence, in contrast to the unceasing chanting of Glorias that had been their former employment. But it is not in the nature of angels to be silent.

A counterproposal was that the angels affirm chaos. There were to be five great proofs of the existence of chaos, of which the first was the abscence of God. The other four could surely be located. The work of definition and explication could, if done nicely enough, occupy the angels forever, as the contrary work has occupied human theologians. But there is not much enthusiasm for chaos among the angels.

The most serious because most radical proposal considered by the angels was refusal –that they would remove themselves from being, not be. The tremendous dignity that would accrue to the angels by this act was felt to be a manifestation of spiritual pride. Refusal was refused.

There were other suggestions, more subtle and complicated, less so, none overwhelmingly attractive.

I saw a famous angel on television; his garments glistened as if with light. He talked about the situation of angels now. Angels, he said are like men in some ways. The problem of adoration is felt to be central. He said that for a time the angels had tried adoring each other, as we do, but had found it, finally, “not enough.” He said they are continuing to search for a new principle.

Published originally in The New Yorker, August 9, 1969