Why Isn’t Everyone an Atheist?

Why does religion persist? We live in an overwhelmingly secular world. Religious practices play little to no role in day to day life any more, at least not in the rich countries. If we have a medical problem the normal solution involves a modern doctor who does not use divination for diagnosis nor prayer for treatment. If the doctor has religious beliefs or affiliations with a church, we expect that to play no part in the treatment.

If we have a dispute we do not go to the local religious leader. We can use courts or mediation services for that. We expect separation of church and state. In fact, we expect separation of church and school, church and science, church and the economy, as well as church and medicine or church and psychotherapy. We can live our entire lives without recourse to religion. And most of us do.

So if religion is unnecessary for life, why isn’t everyone an atheist? Why doesn’t everyone just admit openly what day to day life is telling us loudly: there is no need for religion, and we should find a way to do without it?

In fact, according to the Pew Research National Public Opinion Reference Survey, religious affiliation is plummeting, while the number of religiously unaffiliated adults is rising. The “Nones,” those who do not self-identify with any religious sect, are now around 29% of the US population, while born-again and evangelical Christians (the largest religious cohort) are around 24%. So in the United States the Nones are a larger group than any organized religious sect! And the graph of these trends does not show a roller-coaster of up and down, but a straight line of development- up for the Nones and down for the Christians.

That is encouraging news. And yet, the number of atheists remains quite small and anti-atheist bigotry is still socially acceptable. The Nones include many people with vague and muddled beliefs, as well as New Agers chasing crystals and essential oils. There may be Q-anon adherents in that group, although the evidence suggests that they are more likely to be Christians.

And let’s keep this as simple as possible. Let’s drop the word atheist. I know many people who act as though they don’t believe in God have trouble calling themselves atheist. Let’s just ask why people can’t have a worldview more closely aligned with the secular realities of modern life?

Perhaps I am giving atheists too much credit, but I believe that as a rule we have a worldview that is based on evidence discernible to the senses and confirmable by basic scientific method. Also, an evolutionary worldview that is open to changing ideas according to new evidence. And finally, a worldview that recognizes the consistency of life and natural phenomena and is extremely skeptical of miracles. A worldview with the default attitude that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. And finally, I assume that atheists see humanity, for all its faults, as a cohort of imperfect beings striving to do better, rather than totally depraved sinners who will only do right when they are restrained or blackmailed.

If we all had a worldview such as I described I wouldn’t care what you called it. In such a world, Donald Trump would never have been elected president, Q-anon would have been a joke no one took seriously, and we would perhaps be having thoughtful discussions on how to deal with all the problems that have accumulated in the world which are screaming for solutions. Instead, we see widespread social insanity, which I believe is the result of people holding world views that are radically out of sync with social reality.

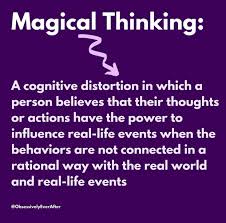

So why do people persist in holding views that are not evidence-based and which cannot stand the scrutiny of simple scientific method (observation, analysis, experiment)? No one has the definitive answer to this question, but I think I see a clue in the 2004 memoir by Joan Didion, The Year of Magical Thinking.

Didion’s memoir is an account of the year following the sudden death of her husband from a massive heart attack. The trauma of shock and grief plunged her into a year of delusional thinking so powerful

that she could not even acknowledge the reality of death. She describes this year in powerful and chilling detail. This is not grief as it is conventionally presented- neatly packaged in stages, managed by soothing, competent professionals and appropriate ceremonies. This is raw, overwhelming trauma which plunges her into a vortex of insanity in which her mind is filled with thoughts of what she must and must not do in order to bring her husband back.

The experiences Didion describes are all the more striking because it is obvious that she is normally a modern, literate, secular person who is obviously successful in navigating the modern, secular world. She tells us repeatedly how successfully she (and her husband) have navigated the worlds of Hollywood and New York, as successful screenwriters and literary critics, how she lives in Malibu and the Upper East Side of Manhattan, socializes with movie stars, shops in expensive boutiques I have never heard of, routinely eats in restaurants I have also never heard of, and travels to Paris to have fun when she and her husband feel like it.

In the face of death, none of this matters. Let me make myself clear. Of course I knew he was dead. Of course I had already delivered the definitive news to The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. Yet I was myself in no way prepared to accept this news as final: there was a level on which I believed that whatever had happened remained open to revision.

That was why I needed to be alone. I needed to be alone so that he could come back.

That was the beginning of my year of magical thinking.

Magical thinking. When I was a kid we called it superstition, and it was something we assumed only affected ignorant, backward people, or people from “primitive” cultures. Others, not modern, literate people like my family and peers. But as it turns out, the world is not so neatly divided into “modern” cultures and “primitive” cultures as we wanted to think in the late 19th century heyday of Eurocentric anthropology. In the face of death we are all primitives trying to look modern.

She is unable to give away her husband’s shoes.

I stood there a moment, then realized why: he would need shoes if he were to return.The recognition of this thought by no means eradicated the thought.

We are not primarily modern, rational, secular beings. We are primarily emotional beings who can maintain our modern, rational, secular facade as long as life is proceeding smoothly. But primal fear and trauma can drag us down into what she calls the vortex of magical thinking in an instant.

So what does all this have to do with atheists and the persistence of religion? I think it has to do with the most primal human need of all- the need to have control over our conditions, our worlds, our lives.You might argue that the need for love is more primal, perhaps that is true. But consider this: if we feel that we have no love, we are unhappy, perhaps deeply unhappy, even depressed. If we feel that we have no control we are terrified.

Joan Didion was a control freak. She was obsessed with being in control- of her life and the safety and comfort of her family. She obsessed over keeping her daughter and her husband safe and became unhinged when she could not do it. Her inability to control death plunged her into the vortex of magical thinking, completely overwhelming her rational mind.

Her reaction was completely normal. Insane, but normal. And here is the clue to the persistence of religion. Religion claims it can conquer death, or at least manage it so that it is not devastating. This is a powerful claim. Religion offers a magical way to maintain control, in the face of all experience, if one only believes. This is powerful, and atheism does not offer anything nearly as emotionally satisfying.

The need for control leads us, I think, to another clue to the persistence of religion: miracles. Every religion has miracle stories. Whether there is one god or many, whether the god is angry or benevolent, whether the religion teaches tolerance or bigotry, they all contain accounts of miracles. I believe miracles are the essence of religion.

It is strange to think of miracles as the essence of religion, because they seem to be the weakest link in the chain of religious tradition. Anyone who has ever studied logic will tell you that it is extremely difficult, in fact impossible, to prove the non-existence of something (for instance, God). We can argue that the probability of the God stories being literally true is vanishingly small, but we cannot actually prove the non-existence of God, any more than we can prove the non-existence of ghosts or extraterrestrials, etc. So if believers want to cling to the concept of God, non-believers cannot actually prove Its non-existence.

On the other hand, the consistency of natural phenomena is rock solid. All of recorded human experience, and all measurements of natural phenomena, confirm the consistency of natural phenomena. There is no reliable account of a miracle. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof, and that is simply not possible in the case of miracles. And without miracles, what is the attraction of religion? The conquest of death is a delusional hope, brought on by trauma and grief. Perhaps fifteen billion humans have lived. Every single one that was alive one hundred and twenty years ago is dead now. No exceptions. None came back after death. There is no reliable account of a miracle. If religion cannot conquer death, what good is it?

But if there is no evidence for the existence of miracles there is abundant evidence of the human NEED for miracles. The desperate drive to control what we cannot control creates an endless appetite for supernatural beings with power to suspend the consistency of natural phenomena, and who may, under prescribed conditions, use this power on our behalf in various emotionally satisfying ways, including overriding death.

Even when we give up religion we often do not give up miracles. If the Nones outnumber the evangelicals, many of them are still flocking to the theaters to see the latest offering from the Marvel Universe. We can do without God, but not without superheroes. It seems that we have a deep need for magical thinking. Didion’s delusional thinking is an extreme case, brought on by shock and trauma. But once we consider this vortex, as she calls it, we start to see that it is not so far from the thinking of normal, day to day life. Casinos make billions from people who prefer magical thinking to the calculations of the law of averages. The advertising industry is entirely based on the human penchant for magical thinking. Hollywood? Television? Netflix? Don’t even start.

The cold, rather depressing fact is that magical thinking is more emotionally satisfying than rational, logical thinking. Shock and trauma can send magical thinking spinning out of control, but even when we are operating within the logic of a world created by money relations and science-based technology we still crave magic and struggle to distinguish our fantasies from reality. It is frustrating to think that people cannot complete the journey from religious orthodoxy to atheism but are likely to wander in a Neverland in between, protected by the world made by evidence-based science and technology, but indulging in fantasies and magical thinking along the way. It would be much more satisfying to imagine a world where everyone is a calm, reasonable atheist. But wouldn’t that at best be wishful thinking? Or just more magical thinking?

Robert Wilfong reporting for The Humanist Advocate

April 1, 2022