Barking Mad D.o.G. Theology

The Madman “Whither is God: he cried.

“I shall tell you. We have killed him—you and I. All of us are his murderers”…..Do we not hear anything yet of the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God?…God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him….What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must not we ourselves become gods simply to seem worthy of it?” Friedrich Nietzsche from The Gay Science

Q.What do you get when you cross an agnostic, a dyslexic, and an insomniac? A. Someone who lies awake at night wondering if there is a doG.—Groucho Marx

Since secular humanism is, in part, “about” religion and the metaphysical concepts of gods and supernatural agency in its denial of their validity, it also necessarily involves itself with ideas that would also be categorized as “theology.” It would follow that anyone commited in some degree to secular humanism concerns themselves also with theology, whether nibbling around the edges of some of the absurd or harmful consequences of this religion or, on the other hand, devotes a lot of time into the exploration of the foundations and varieties of them. Given that, take a look back at a theological movement from mid-twentieth century history, a movement named interchangeably radical theology, Christian atheism, and Death of God theology ( hereafter, D.o.G.) Now that’s the kind theology we should be able to get our heads around.

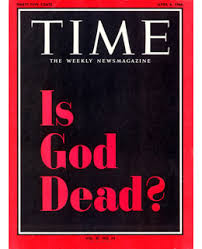

It may be a stretch to call the contributions of thought by a group of primarily four or five main theologians and philosopher a “movement,” but that title may be partially the responsibility of John Elson, a writer in Time magazine when he wrote a report in the October, 1965 edition of the publication entitled “The Death of God Movement.” A follow-up article, published April 8 , 1966, became a national sensation, not so much to the content or its title “Towards a Hidden God,” but for the magazine’s bold, black cover with a red font large enough to cover it. That issue remains Time’s best selling ever.

Whether Death of God theology was large or influential enough to be called a movement is highly debatable, but ideas that spawned it were beginning to be formulated much earlier, according to scholar William R. Hutchinson, who writes that “many mainstream American Protestants starting in the nineteenth century encouraged seminaries to develop an approach to religion that went beyond Christianity, setting groundwork for the paradox of ‘atheist theology'”. “This movement gave expression to an idea that had been incipient in Western philosophy and theology for some time, the suggestion that the reality of a transcendent God at best could not be known and at worst did not exist at all.” ¹ The increasing rationalization of social and economic relations, the beginning of the creation of large amounts of wealth among wider populations, and the conquering of many diseases—all leading to less grim lives— led the collective modern man to the secular understanding that abstract, supernatural, or mythical forces were becoming less significant, or even meaningless, as far as life in the real world went. Some revisions in the basic tenets of Christianity might be required, believed the seminarian academics, if it was to survive the secular challenge.

And a revision including a dead God, or transplanted God seemed to be a natural end for most of the radical theologians. Here, from a web post, is a paraphrase of author and D.o.G. theologian S. N. Gundry’s short synopsis of some of the main movers of the era.

Thomas J. J. Altizer believed that God had actually died.To say that God has died is to say that It has ceased to exist as a transcendent, supernatural being. Rather, It has become fully immanent in the world. The result is an essential identity between the human and the divine. There’s that transplant thing. But the church keeps trying to put It back in his transcendent kingdom. Christians must now will Its death so the transcendent becomes immanent in the world. A mystical transplantation and heady stuff, to be sure. Altizer also engaged in Buddhist teachings, so his writings didn’t always follow Western rules of thought.

William Hamilton took a more pragmatic position that the previously alluded to “rationalization” of modern society reflected many citizens feeling that previous theistic explanations about the workings of the world were being replaced by nontheistic ones, and that they increasingly no longer “accepted the reality of God or the meaningfulness about him,” and that this trend was irreversible. For Hamilton, God’s death must be affirmed and people must come to terms with the cultural and historical end of it. This might be the most credible explanation for writing God off as a force in the universe, especially the all-powerful one that was once attributed to it.

Paul van Buren took the empirical analytical philosopher’s approach that “real knowledge and meaning can be conveyed by language that is empirically verifiable. This is a tough test to pass, especially for something like a transcendental god that can’t be verified by any of the five senses, and also difficult to make a credible objection to. Gundry says it is hard to find anything in van Buren’s The Secular Meaning of the Gospel Based on an Analysis of Its Language that would suggest that van Buren is “anything but a secularist trying to translate Christian ethical values in that language game.”

These and others in that school of thought believed that religion (specifically Christianity) has served a purpose by tending a natural need of man for spirituality, a sense of finality in the search of a foundation from which all questions about have been, or could be answered, and the origin of a moral code. Most of them recommended staying the course with the gospel of Jesus to as a moral code, and for its message of love, hope, and charity.

So why isn’t this outlook called an anti-theology? After all, secular humanism has no argument about the merits of most of the Christian code for living. In fact, a common criticism of secular humanism is that it is a lot like Christianity on that score. But humanism need not first shed its earlier commitments to god or mythical magicians of any flavor since it had none to begin with. The argument that humanism got its morals from Biblical moral code, or its optimistic outlook about the improvability of the human condition through reason and science is just a substitute for or replaces the Christian concept of salvation is just wrong.

The difference, writes Andrew Seidel, author and attorney with the Freedom from Religion Foundation, “This is not because all religion is correct or because all religion is man-made. There are some universal human principles that the human authors of religion can’t help but put into their religion. Don’t steal, kill, or lie; treat others as you’d like to be treated; help those who can’t help themselves. But these are not religious principles. These are universal human principles, and you must jettison the religious from the humane. Humans need saving, but they need to be saved from religion.” ²

And, I would add, humans need saving from D.o.G. theology and its gravediggers: it’s a false theology disguised as philosophically sound, and a hopelessly confused construction that works for neither the secularist—who can only find it amusing—or to the believer who is stripped of a foundation of everything which she desperately needs without replacing it with the more sound choice of reason and critical thinking.

¹Simon, Ed. “”The Death of God, Again,” America and Other Fictions. Hampshire, UK: Zero Books, 2018.

²Seidel, Andrew. The Founding Myth: Why Christian Nationalism Is Un-American. New York: Sterling Publishing Company, 2019. NOSHA was fortunate to have hosted a book signing event for this book and a lively presentation by Mr. Seidel on the campus of the University of New Orleans in January of this year.

Marty Bankson reporting for The Humanist Advocate

February 19, 2020